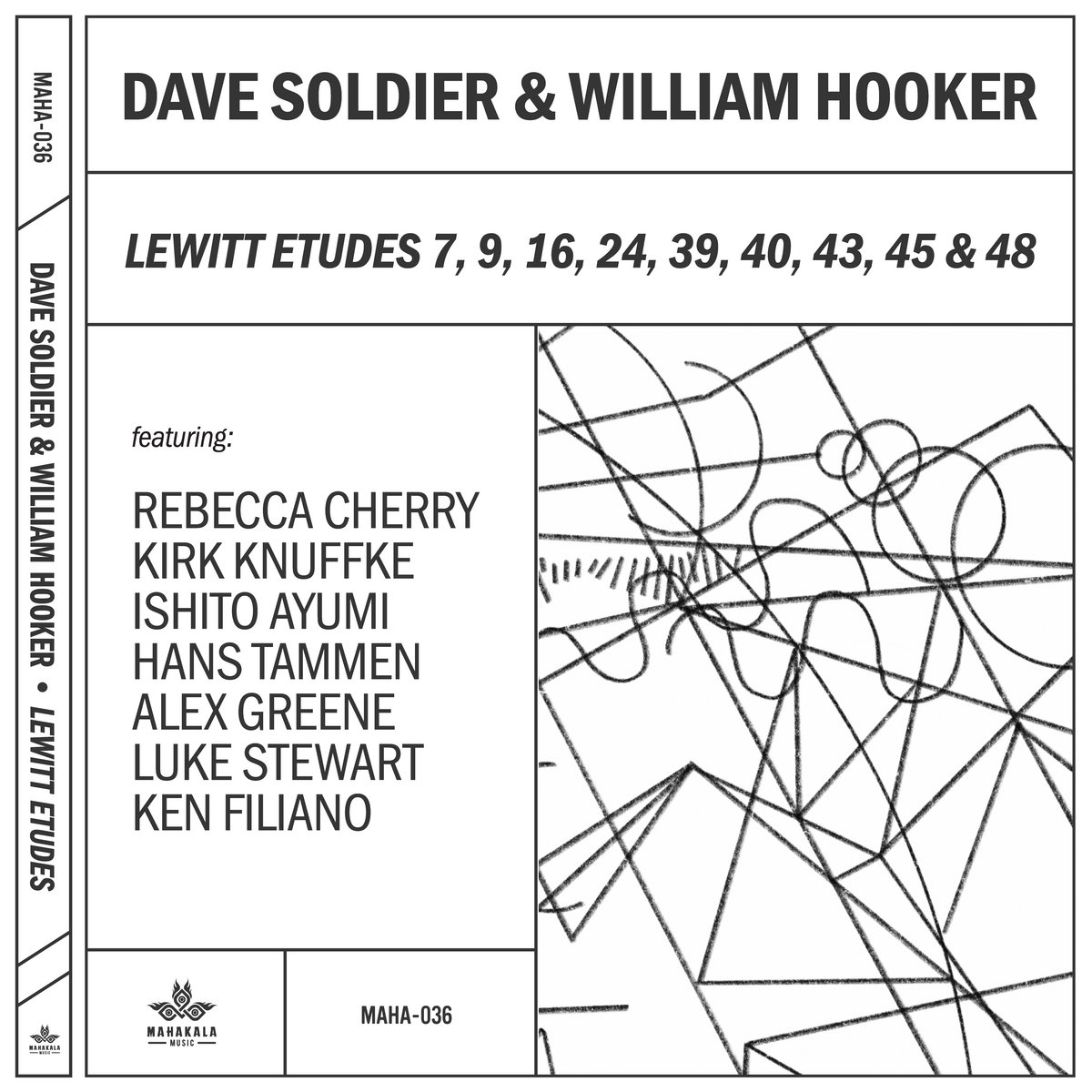

David Soldier & William Hooker: The LeWitt Etudes

Mahakala Music MAHA 036, recorded April 2022, released Oct 2022. Total Time: 71:54 Minutes. With David Soldier, William Hooker, Rebecca Cherry, Kirk Knuffke, Ayumi Ishito, Hans Tammen, Alex Greene, Luke Stewart, Ken Filiano. Recorded by Parichat Songmuang, Dolan Studios, NYU, mastered by Gene Paul.

Grains of Sand Bringing Sonic Pearls:

Dave Soldier and William Hooker present LeWitt Etudes 7, 9, 16, 24, 39, 40, 43, 45 & 48 The first sounds leaping from your speakers when you play this album are two upright bass lines, one grounded in blues grooves and harmony, the other freely vocalizing with sinuous interjections from high on the neck. Right out of the gate, the twin voices foreshadow the extreme contrasts explored in this interpretation of Dave Soldier's LeWitt Etudes: Fifty Architectural Designs for Musicians (2015, Op. 34), namely selections 7, 9, 16, 24, 39, 40, 43, 45 and 48. The etudes, emulating rules for visual artists set down in Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawings series, are brief prompts for improvisers that deftly bring shape to collective compositions. For this album, a nine-piece ensemble gathered in the spring of 2022 to collectively compose in just this manner, over three hours at New York University's Dolan Studios. Their performance seamlessly blends the harmonies, groove and coordination of arranged music with the unfettered sonic sculpture of seasoned improvisers. And while others have interpreted the LeWitt Etudes, this latest recording by Soldier and William Hooker, under the Mahakala Music imprint, stands as the work's finest manifestation yet.

Hooker, a trailblazing, genre-defying drummer in New York's free improvisation scene since the mid '70s, feels the chemistry between the players and the resulting music lends this album historical significance. “This project was pretty damned heavy,” he says. “I think it makes a dent in the music of the 21st Century. I hope people worldwide, speaking other languages, can hear this music. That's my purpose now.”

The music's universal appeal is clear: simply hearing the instrumental odyssey, without intellectual trappings, is inherently compelling, as the richness of each instrument's tonal possibilities comes to the fore, beautifully recorded and mixed by engineer Parichat Songmuang, mastered for maximum clarity by Gene Paul. The musicians' melodic arcs, growls, sighs and drones — built on the sounds of wood and string, reed and mouthpiece, oscillating electric voltages, and sticks on skins — create a smorgasbord of sound beyond the realm of language or even most other music.

But the chemistry in the room that day didn't come from nowhere. Soldier and Hooker have been making music together for decades. “Dave and I have four albums out together,” says Hooker. “We've done a lot of work together, and I don't separate the LeWitt Etudes from any of the work we've done so far.” Rather, it's a continuation of a years-long dialogue between them, with Hooker's drum kit and Soldier's violin, mandolin, and five string banjo bringing multiple voices to their conversation on this album.

From there, the collaborators added other voices to their palette: In one corner were the aforementioned bassists, Luke Stewart (recently named one of the 25 most influential jazz artists of his generation by Downbeat magazine) and Ken Filiano (both an orchestral double bassist and a pillar of New York's jazz scene for decades), their weave of slapping, deep tones and whispering harmonics perfectly complementing the dynamics of Hooker's drumming. Beside them, Hans Tammen, renowned for multiple projects from Endangered Guitar to the Dark Circuits Orchestra, sat playing either a “big fat jazz guitar that's older than me,” as he puts it, or a Buchla synthesizer.

Further spaced around the tracking room were Dave Soldier, his three instruments at the ready; Rebecca Cherry, a violinist deeply versed in the classical canon, yet with an adventurous streak; Kirk Knuffke, with 18 albums under his name, dubbed by the New York Times “one of New York City’s busiest musicians,” on cornet; Ayumi Ishito, who's new Open Question project has received glowing reviews, on tenor saxophone; composer Alex Greene, a thirty-year veteran of the Memphis indie rock and jazz scene, on piano; and William Hooker, whose thunderous-yet-nuanced drumming had a profound effect on the dynamics of each piece.

Just what sort of score were these seasoned composers and improvisers faced with? The LeWitt Etudes, Soldier explains, “were literally inspired by Sol LeWitt's Wall Drawings.” The visual artist LeWitt devised a rules-based approach to creative projects in the late '60s. His Wall Drawing No. 26, for example, reads: A one-inch grid covering a 36 inch square. Within each one-inch square, there is a line in one of the four directions.

The open-ended possibilties of such guidelines fired Soldier's imagination. “Within LeWitt's rules, there are many ways you can realize them,” he reflects. “So why can't music be made the same way?”

While Soldier has scored thousands of pieces with standard notation, from avant garde operas to arrangements for rock bands, in this case he emulated LeWitt's rules with purely textual guidelines, “to foster adventures in musical group compostions by players from any tradition at any level of training including none,” as he writes in the introduction.

The two words, “including none,” hint at what made this approach so intriguing to Soldier. “Writing the etudes grew partly from my experience with doing things like working with Thai elephants. How do you get elephants to play music? You have to work with their mahouts, their handlers. They don't know how to read music, so we do it with stories. That's also how I did those kids' records, like the Tangerine Awkestra with kids from Brooklyn, or Yol K'u, with Mayan kids in Guatemala.”

That approach also echoes the guided improvisational strategies Soldier encountered in the downtown New York avant garde scene. “Butch Morris led a lot of groups with a thing he called 'conduction.' He wouldn't write anything down, but he would conduct people with hand signals. And in the 80s when I moved to New York, I played in his band — the violin section was Billy Bang, Jason Hwang, and me. And Pauline Oliveros was definitely an inspiration for the LeWitt Etudes as well.”

And so these novice-friendly pieces are also compelling to seasoned musicians. What player would not be intrigued by instructions to play “the most lonesome possible solo,” as in LeWitt Etude #43 (After Hank Williams)? Or by #44 (After Pauline Oliveros), “the players walk through the hall trading pitches with each other and with the audience members”? Indeed, the complete collection of etudes makes for an intriguing, intricate, and even comical read.

“My own instructions get kind of humorous and down home,” says Soldier. “That's just my personality. LeWitt's are more like, 'You will draw these circles, you will attach them at right angles.' With mine, you can change the rules, just like we changed the rules in our recording session,” says Soldier. “The major rule is, it has to be music that you want to listen to. You don't want to just play any nonsense.” Curious listeners can read the LeWitt Etudes score in full at davesoldier.com, or peruse the cover art for the nine etudes salient to this album. Better yet, just listen — and try to tease out the logic governing each piece, as players dance with the words on the page.

While all the players on this album excel at pulling ideas from thin air, the dynamics and drama that emerge from the etudes' “stories” push their improvisations to new heights. “It's just as great to use great improvisers as it is to use untrained musicians,” notes Soldier. “The difference is, of course, that we could put that whole album together in just three hours.” Indeed, if the crack band assembled by Soldier and Hooker was perched in an oyster shell, each etude a grain of sand tossed in among them, then this album brings you the musical pearls that emerged.