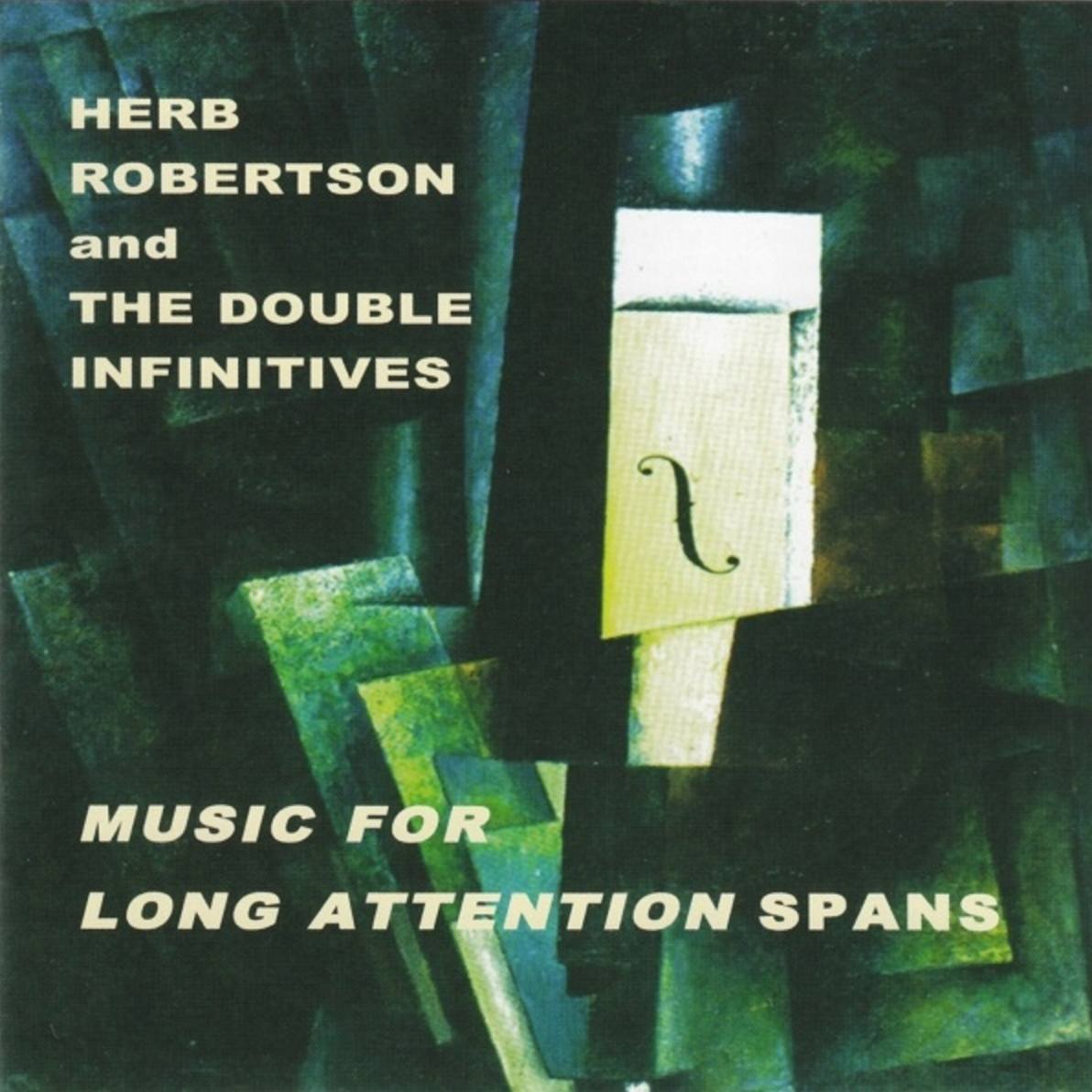

CD HERB ROBERTSON:

MUSIC FOR LONG ATTENTION SPANS

Herb Robertson – trumpet, voice, melodica and other horns, Steve Swell – trombone, cymbalophone, Bob Hovey – trombone, percussion, background vocals, Hans Tammen – endangered guitar, Chris Lough – bass, Tom Sayek – drums, percussion, background vocals.

Buy CD from my website here, preview on iTunes.

Reviews

Joe Milazzi, One Final Note 2001

Herb Robertson’s ensembles have often been brass extravaganzas: his Shades Of Bud Powell features highly unusual arrangements of bop themes for two trumpets, trombone, French horn, tuba and drums; 1991’s Certified is a predominantly violet, Day-Glo impasto of Dave Taylor’s bass trombone, trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn, pocket trumpet, E-flat cornet, valve trombone, and even Robertson’s own burbling, yawping vocalese. Music For Long Attention Spans , with its twinned trombones and thick percussive tissues connecting electric guitar, bass, drums and “little instruments,” is very much a continuation of Robertson’s earlier large-ensemble work. Like Knudstock 2000 on Cadence Jazz Records, in which all these players participate, it also stands somewhat apart from the small-ensemble recordings — both under his own name and with groups such as the one co-led by Joe Fonda and Michael Jefry Stevens — which have raised Robertson’s profile considerably in the past decade.

Robertson’s music is largely cumulative in effect. Dense passages of collective improvisation, whether for horns alone or involving the rhythm section, are juxtaposed against carefully scored melodies and lengthy passages in which much activity takes place at the very boundaries of audibility, both in terms of volume and pitch. Robertson prefers a scale that is less grand than it is simply expansive. There is a line of argument, however, in what sounds like performances that sprawlingly luxuriate in their own refusal of logic and their own disregard for internal differences in scale. Robertson’s orchestrations are not unlike Robert Rauschenberg’s large-scale assemblages and combine paintings, cobbled together as they from stock images, ready-made apparatuses, private associations, older works in the artist’s own canon, and big, splattery demonstrativeness. “Time Out / Zipangu” here is an excellent case in point. The piece opens with Hans Tammen striking gong and cymbal sounds from his guitar (the endangered aspects remain unexplained), over which a long, freely accented melody unfurls. What may sound like spontaneous unison outbursts from Bob Hovey and Steve Swell’s trombones are actually the keys to the piece’s design. Robertson moves into an upper register solo in which he sounds like a man maniacally smacking his lips. Following a guitar solo in which Tammen’s strangled arpeggios build up to screaming whole tones, Robertson uses the softer articulations of whistles and melodica to introduce a new theme that bounces — but with melancholy — in a 6/8 tempo.

The central performance here is the almost 24-minute “Future Perfect” (it ends with the same, lonely piano chord with which it began), a deliberate — not plodding — collective improvisation that toys with the listener’s expectations that the music will ultimately coalesce and work itself up into some sort of hurtling momentum. “Future Perfect” also features Robertson’s most bravura playing on the date. He transforms his instrument into a kazoo; makes it squeal, purr, and chortle; plays beautiful, soaring, almost classically-contoured cries; and works out a Doppler shift effect, with fluffier notes approaching and receding (rising and falling down a scale), only to gradually skew out of equilibrium and become syncopated with ominous growls and squawks. His is an orchestral performance in a work that is much smarter than it seems on its surface.

That said, Robertson is remarkable by his absence as a trumpeter per se on this recording. For some, then, Music For Long Attention Spans might represent something of a disappointment. It is not just that Robertson is often playing percussion, whistles, and small instruments. In fact, on the closing “Beehive Secrets,” Robertson seems purposely to be playing runs that will be lost in the dripping honeycomb that teems with the droning work of the trombones. Nevertheless, this is a true group project, and Robertson’s cohorts more than hold their own. Tammen in particular has a startlingly original command of guitar effects, and, when he references the standard noises, he cracks them open to sift through the sense inside. On “Future Perfect,” for example, there are passages in which Tammen sounds uncannily like a tape running backwards. And on “Tickle Me Crazy,” he even plays phrases that could have been excerpted from a vintage performance by the Raymond Scott Quintette. Chris Lough is equally impressive on bass. Truly, he is the only time-keeping instrument here, primarily responsible for freeing up Tom Sayek to engage in the freedom of color and meter that is necessary to pieces such as “The Status Quo.” Whether engaging in free duets with Steve Swell, squirming with repressed hilarity on the opening of “Tickle Me Crazy,” playing great, Mingus-like slaps on “Time Out / Zipangu,” or crafting a “walking” bass pattern underneath Robertson’s recitation on “The Status Quo” that one would do well to follow throughout the entire piece — it sounds like a man trying to decide in which direction to pace — Lough evinces great strength and sense of purpose. Swell and Hovey, again, are absolutely indispensable to this music. You can often hear the metamorphosing volumes of air and saliva — less Protean, more like Plastic-Man — in the sounds that emerge from the conical bores of their instruments. Unexpectedly, it is possible to tell the men apart, but it is not necessary for enjoyment of the music.

More of a debut for Robertson than the earlier Ancestors (1981), on which he played no solos, the 1983 Mutant Variations (both on Soul Note) remains a key item still in Tim Berne’s diverse, at-times frustrating, discography. Clarence Herb Robertson (as he was then billed) would be Berne’s most important collaborator for much of the 1980’s, and here his plunger-muted cornet pierces through the unison statement on the opening “Icicles” with an utterly distinctive, pent-up sound — a stream of self-mocking, desperate jive projected through the tin of a carny’s megaphone. Almost 20 years later, and one can hear Robertson’s influence on a whole group of players, among them Rajesh Metah, Natsuki Tamura, Greg Kelley and even Cuong Vu, all of whom owe something to Robertson’s vision of brass tonalities marooned somewhere between the organic and the metallic. Underneath the infectious high spirits, the roughhousing, and the superficially zany humor of Robertson’s music, there is a tough and clear-eyed investigative outlook. What Robertson has brought, most surprisingly, is a new and oddly poignant idea of sensuousness to an aesthetic that can too easily traumatize both instruments and the ears of listeners. It is this quality that makes his performances on Berne’s recordings so engrossing, and that same quality permeates Music For Long Attention Spans.

Glen Astarita, All About Jazz 2001

No doubt Herb Robertson is one of the criminally under-recognized trumpeters in modern jazz and free improvisation as his highly praised work with alto saxophonist Tim Berne and recordings for the much beloved “JMT” jazz label will attest to his musical ndividuality. However, Robertson has since charted fertile terrain with some of Europe’s finest, although this new release was recorded in New Jersey, June 11, 2000.

Here, the trumpeter steers a group of like minded musicians for a series of lengthy and largely free improvisational pieces as the band opts for a semi-theatrical approach, teeming with humor and pathos. With “The Status Quo,” Robertson’s poetic recital provides a sense of parody amid trombonists’, Steve Swell and Bob Hovey’s cantankerous mid-register lines and Hans Tammen’s finicky “endangered guitar” underpinnings. Consequently, Robertson perpetuates a plethora of novel propositions via his gruff, raspy tone, fluent lines, and altogether muscular mode of attack. Tammen continues with his manic guitar passages on the free flowing piece, “Time Out/Zipangu,” whereas, various members of the band utilize small percussion instruments in concurrence with Robertson’s melodica performances, whistles and the soloists’ fragmented micro-themes. Hence, there’s a whole lot going on here, including Chris Lough’s nimbly executed bass lines, drummer Tom Sayek’s oscillating rhythms, Robertson’s boisterously stated lyricism and the musicians’ generally festive undercurrents on pieces such as “Tickle Me Crazy” and “Beehive Secrets”.

Overall, Music For Long Attention Spans effectively captures one’s imagination as this new effort might signify one of Herb Robertson’s most persuasive recorded documents to date. Highly recommended.

Richard Cochrane, Musings 2001

This is a jazz band of splendid talents, and this record must be one of the most exciting in the Leo catalogue of those which fall firmly under that generic rubric. Full of unexpected moments, it is genuinely enthralling.

Pablo Abril, Modisti.com 2002

Post-free stances from a textural outlook, featuring a certain deconstruction of instrumental roles, incorporation of noise, unusual distribution of sonic space. A cubist perspective in which the interplay remains quite lucid within free language, displaying a strong tendency towards atmospheric construction.